The roads are narrow and the mass of fellow humans overwhelming. Jostling one’s way through this intractable crowd is a skill only acquired with repeated visits to the place. I didn’t do so badly, considering it was my second trip. Revisiting the pavement book bazaar in Daryaganj, situated in Old Delhi or the other face of the city I call home, brought back snapshots of a winter morning tucked away in the memory files. Nearly a decade ago, I had visited the place for the first time with a co-worker friend. I had been instantly besotted with Booklane.

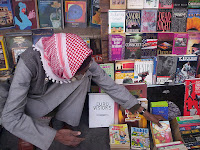

The roads are narrow and the mass of fellow humans overwhelming. Jostling one’s way through this intractable crowd is a skill only acquired with repeated visits to the place. I didn’t do so badly, considering it was my second trip. Revisiting the pavement book bazaar in Daryaganj, situated in Old Delhi or the other face of the city I call home, brought back snapshots of a winter morning tucked away in the memory files. Nearly a decade ago, I had visited the place for the first time with a co-worker friend. I had been instantly besotted with Booklane.On that sunny January morning (or was it December?), my friend had gifted me a trip to this booklover’s promised land. I remember my sense of wonder on seeing this never-ending strip of book stalls, the 200-odd sellers displaying their collections neatly on the pavement and producing your requested book in a jiffy. We spent hours and hours scouring through the books, a lot of them secondhand. One is free to read, not just browse through books in this leisurely atmosphere.

The sun had warmed our feet, the books our hands and hearts, the prices our pockets. The Sunday book bazaar is popular because of the availability of good, even rare books at cheap prices. The memory has faded a bit, but I do remember returning home with a Seamus Heaney anthology and a book of plays, biographies and other interesting details, put together by the National School of Drama or NSD. Both prized possessions to this day. Without a doubt, that winter’s day happened to be one of the brightest in my life.

The sun had warmed our feet, the books our hands and hearts, the prices our pockets. The Sunday book bazaar is popular because of the availability of good, even rare books at cheap prices. The memory has faded a bit, but I do remember returning home with a Seamus Heaney anthology and a book of plays, biographies and other interesting details, put together by the National School of Drama or NSD. Both prized possessions to this day. Without a doubt, that winter’s day happened to be one of the brightest in my life. My visit to Booklane last Sunday wasn’t as merry, though. It appeared the area for the book bazaar has shrunk a bit, and this time, it was really a battle to make one's way through the crowd. Even when my feet landed at a spot that would let me look at the books, the view was anything but happy. For most of the stalls were packed with textbooks of all sorts. Students thronged the place, picking up fat books at cheap prices. The fiction lover was virtually non-existent. Coin lovers weren’t, though, because this is also a great venue to buy old coins dating back to the era of the British Raj.

My visit to Booklane last Sunday wasn’t as merry, though. It appeared the area for the book bazaar has shrunk a bit, and this time, it was really a battle to make one's way through the crowd. Even when my feet landed at a spot that would let me look at the books, the view was anything but happy. For most of the stalls were packed with textbooks of all sorts. Students thronged the place, picking up fat books at cheap prices. The fiction lover was virtually non-existent. Coin lovers weren’t, though, because this is also a great venue to buy old coins dating back to the era of the British Raj.Although the trip to Booklane wasn’t all that satisfying, the jaunt to Old Delhi was immensely fulfilling. For here is a world sheltering a culture and a history that has almost ebbed out of the modern city life I witness every day. And amid all the crowd and congestion lies a charm that keeps calling you to the place again and again. Yes, more trips planned to the walled city.

Special thanks to Bhupinder for making me Booklane bound.